|

The

emergence of global business systems, and along with it the need

for protection of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) are now

almost foregone conclusions. But what caused them? There are at

least two obvious factors that contributed to this changed global

political economy and the concomitant introduction of IPR. By the

early 1970s, the high labor costs in the OECD (Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development) countries had led to the

relocation of labor intensive industries to third world countries,

which saw the beginning of transition from a manufacturing based

economy to a service based economy dominated by

knowledge-intensive industries.

On the other hand, the condition of indebtedness of the Third

World of the 1970s (because of the twin oil crises of 1973-74 and

1979) created an increased demand for foreign investments. Both

these factors fed on each other, resulting in an increased

prominence of transnational companies (TNCs) in the global trade.

For the latter, it was clear that while this situation could lead

to higher revenues, the strategic route lay in enforcing a strict

IPR regime.

In the eighth round of GATT talks (1986-1993), initial attempts by

the United States to introduce a Trade Related Intellectual

Property Rights (TRIPS) regime brought forth strong objections

from the third world countries like India and Brazil. Their

apprehension was that the technology they needed from the west for

development would become more expensive under an active TRIPS

regime. However, in 1988 a compromise was arrived at with certain

trade concessions made by first world countries.

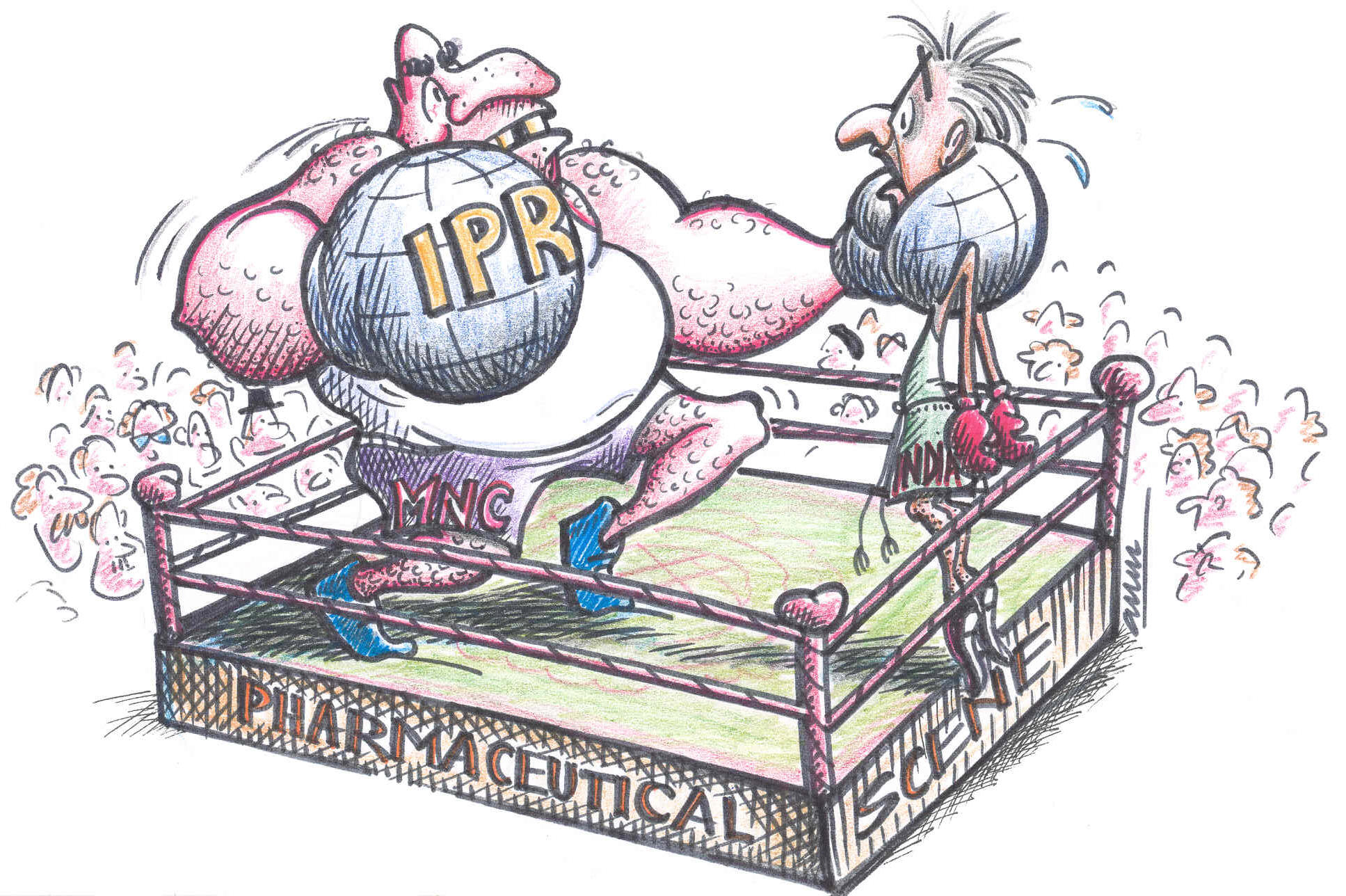

For a country like India, the sector that is likely to be affected

strongly by an IPR regime, (more particularly with respect to

product patenting), is the pharmaceutical industry. The impact may

be felt either through direct competition or via patenting of

Indian tropical bio-diversity by transnational companies. Therefore,

an urgent need for policies and strategies to combat the

situation.

India has made significant strides in terms of

self-reliance in pharmaceutical products. From being an

importer of medicines in the first few decades after independence,

today we are able to meet a good part of our essential requirement

through indigenous production. Prices of indigenously manufactured

drugs, once among the highest, are among the lowest in the world

today. A net foreign exchange earner, with the annual turnover of Rs. 15,000 crores, the Indian pharmaceutical industry today ranks

among the most developed in the third world, in terms of

technology, quality and range of pharmaceuticals manufactured. The

annual increase in the drug production is about 15% , while the

average pre-tax profits for the industry is 8% of the annual

sales. Nevertheless, the share of Indian pharmaceutical business

in the present world market is only 1%, which suggests

considerable opportunities for growth.

The reason for the low price of Indian drugs is twofold. First, as

a result of a government intervention through the Drug Price

Control Order (DPCO), the prices of all bulk drugs and thousands

of formulations have been controlled so as to make them affordable

to the common man. Secondly, and perhaps more significantly, many

Indian companies – particularly, during the early period of the

industry’s growth - have engaged in reverse engineering, a process

that has allowed quick replication of new drugs at a low cost.

But today with an impending strong IPR regime, the major issue

facing the domestic industry is that of investing in R&D so as to

better compete with international corporations in creating new

drugs. The industry’s R & D expenditure is currently about 2% of

its annual turnover - considerably less than the 6-8% spent by

many corporations in the western world. The cost of pharmaceutical

R&D in the developed world is a steep one - around $250-300

million per annum. In India, however, the expenditure might be

only one third to one fourth of the last figure, primarily because

of the low manpower costs. |

Few Indian companies can afford to spend in excess of Rs.100 crores

in R&D and wait for a decade for pay back. Essentially, a basic

research program demands a high “entry fee”, which only companies

with very deep pockets,

large

business volumes, and an extensive

global operation are positioned to accept!

According to the U.S industry, it loses nearly $1.4 billion

annually from the sale of copied drugs in just four third world

countries including India —which has a $0.92 billion share of the

copying. It is difficult to eschew entirely the truth of this

criticism. The moot point, however, is whether the high R&D costs

borne by TNCs alone can legitimize the imposition of a strong IPR

regime. For, amongst other things, historically most first world

countries have introduced product patents only after their own

pharmaceutical industries became strong enough to challenge

international competition.

It would thus appear that the imposition of a strong IPR regime is

more an attempt by western countries and their pharmaceutical

corporations to consolidate the gains they have made in the last

several decades. Just when Indian pharmaceutical companies are

beginning to acquire strength under the process patent regime they

are being forced to concede the gains to transnationals. Of

course, this need not imply that the Indian sector should be

provided a completely protectionist environment indefinitely;

rather there should be a time frame arrived after due

consultations with the industry. Presently our timeframes are

dictated by the external environment and therefore does not do

justice to our internal concerns.Some of the adverse changes that

could affect the Indian pharmaceutical industry under the IPR

regime are: increased R&D expenditure and hence higher Indian drug

prices, and lower export of drugs because of the inability to use

process patents. Overall, however, the use of IPR will not be an

unmitigated disaster if the industry invests well in basic

research, new product launches, a thrust into global generics

market and licensing-in of products from companies that do not

have a presence in India. There needs to be rapid development of

innovative, non-infringing processes for products going off-patent

internationally and a leveraging of the low cost domestic

manufacturing. In an ironic sense, India has already benefited

from an impending IPR regime. For, with the recent attempts by

western players at patenting age-old Indian botanicals such as

neem, turmeric, jar amla and several others, Indian policy makers

have suddenly woken up to the advantages of patenting our

bio-diversity!

There is no doubt that bio-diversity will increasingly gain

importance in drug development. Developing countries, like India

and Brazil, are the source of an estimated 90% of the world’s

store of biological resources. More than half of the world’s most

frequently prescribed drugs are derived from plants or synthetic

copies of plant chemicals — and this trend is growing. It has been

estimated that even if just a 2% royalty were charged on genetic

resources developed by local innovators in the tropical countries

of the South, the North would owe around $5 billion / year in unpaid

royalties for medicinal plants.

To conclude, the use of IPR in the Indian pharmaceutical industry

must be perceived judiciously in light of its strengths and

weaknesses. The role of the government must be more bold and

imaginative in dealing with the industry’s problems and

opportunities.

|